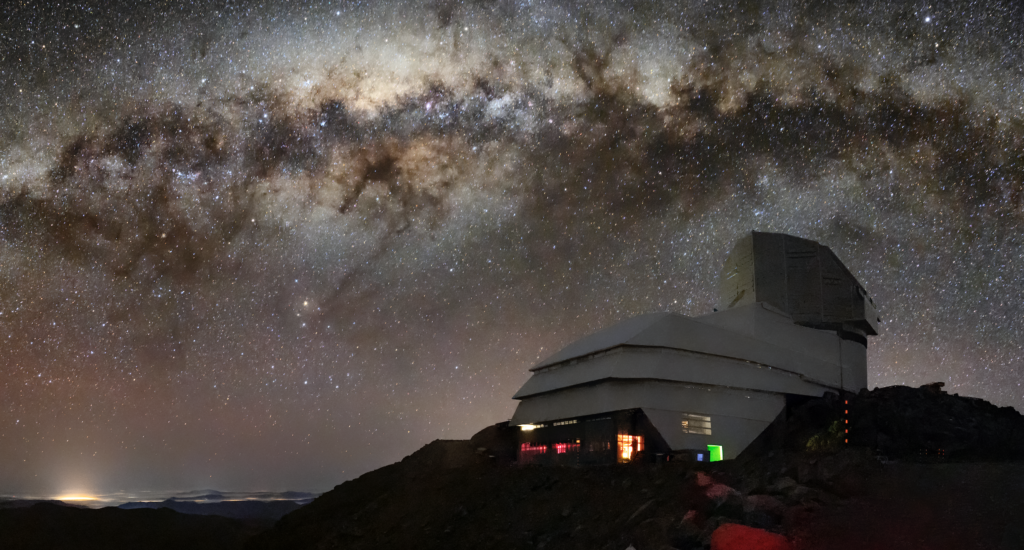

Last Wednesday, the UW planetarium became the epicenter of excitement and discovery, hosting an event that left attendees starry-eyed and inspired. The evening was filled with captivating presentations about current and anticipated discoveries with the Vera C. Rubin Observatory which is currently in the last phase of the construction in Chile.

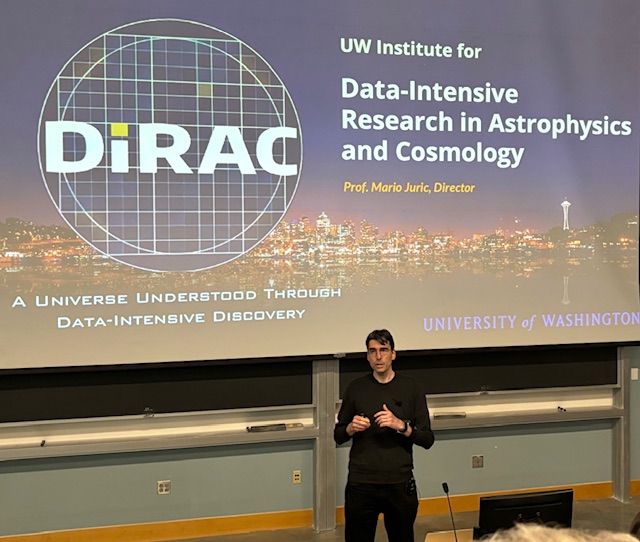

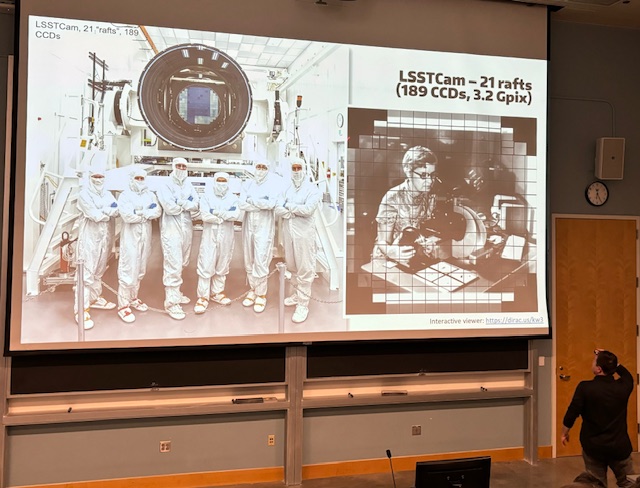

As guests arrived, they were greeted by the DiRAC team. The lobby buzzed with conversations about the evening’s program. The event kicked off with a warm welcome from Prof. Mario Juric, DiRAC director, who highlighted the importance of community engagement in the pursuit of scientific knowledge. Followed by the latest updates from Prof. Zeljko Ivezic, Rubin Observatory Construction Project Director. Prof. Ivezic took to the stage to introduce this cutting-edge observatory, which promises to revolutionize our understanding of the universe. Equipped with the latest in telescope technology, this observatory will allow scientists to look deeper into space than ever before.

UW Planetarium

DiRAC Reception

Prof. Juric Presentation

LSST Camera | Vera C. Rubin

Andy Tzanidakis

Graduate Student

UW Planetarium Coordinator

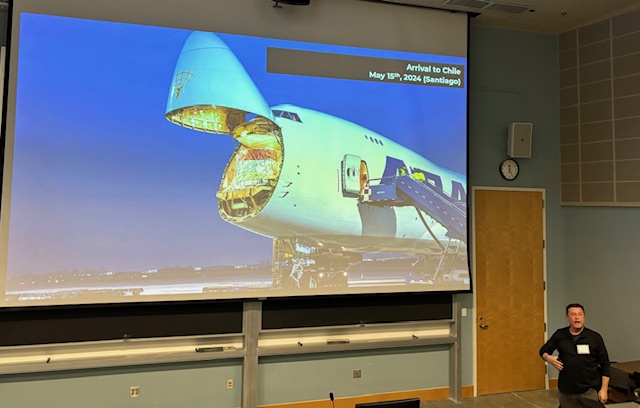

LSST Camera Transportation from USA to Chile

Prof. Željko Ivezic

The Planetarium Experience

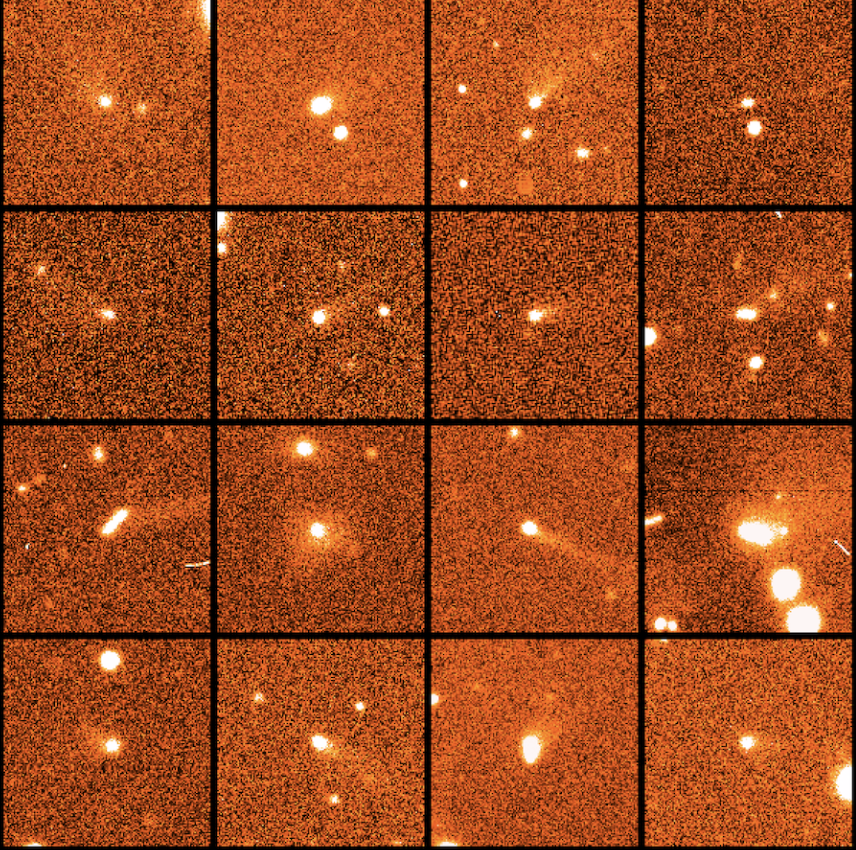

The highlight of the night was the planetarium experience led by Prof. Andy Connolly. The presentation detailed how the observatory’s advanced camera would enable the discovery, the study of distant galaxies, and the exploration of cosmic phenomena that have long puzzled astronomers. The audience was treated to stunning visuals of the observatory’s capabilities, and the excitement in the room was wonderful to experience.

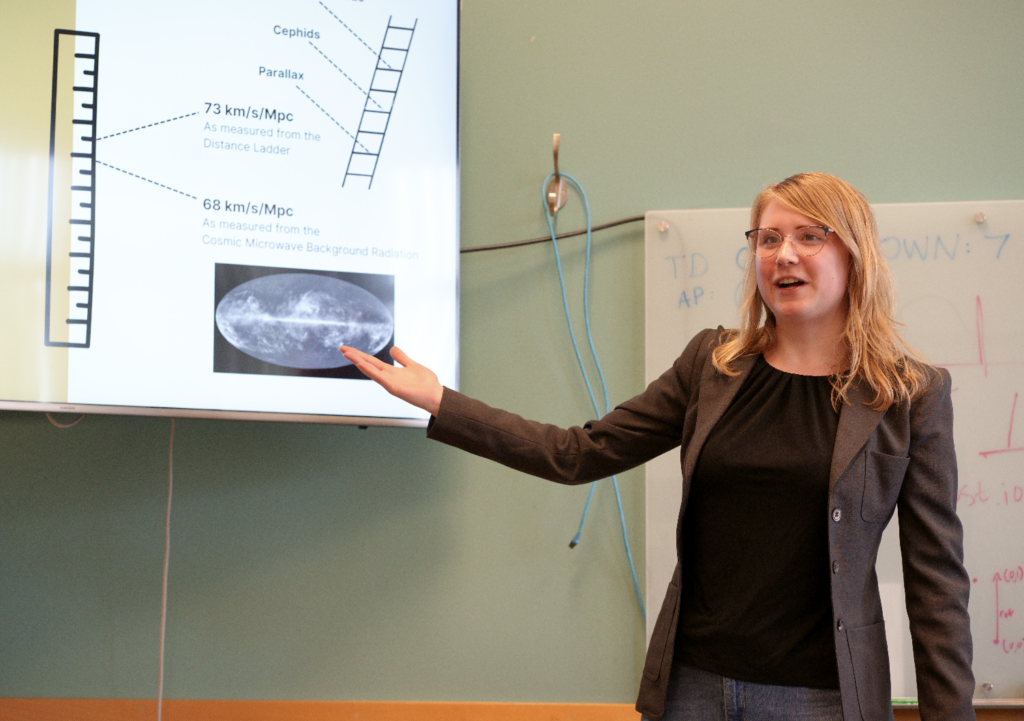

Engaging Presentations

Following the planetarium show, a series of presentations captivated the audience. Each talk was a quick dive into one segment that Rubin will help us understand. Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) were the topic of this session. It was designed to educate and inspire. The audience was left in awe, with many expressing a newfound appreciation for the unknown of our universe.

Interactive Q&A Sessions

The event also featured interactive Q&A sessions, where attendees had the opportunity to ask questions and engage with the experts. These sessions sparked lively discussions and provided deeper insights into the topics covered. It was clear that the audience was eager to learn, with questions ranging from the technical aspects of the new observatory to the implications of recent discoveries.

Aren Heinze

Aren Heinze

Joachim Moeyens

Joachim Moeyens

Colin Orion Chandler

Colin Orion Chandler

Prof. Mario Jurić

Prof. Mario Juric

Prof. Andy Connolly

Prof. Andy Connolly

Prof. Željko Ivezić

Prof. Zeljko Ivezic

Looking to the Future

We’d like to take this opportunity to thank again everyone for their participation and to emphasize the importance of public support for scientific endeavors and encouraged everyone to stay curious and engaged.

The planetarium event was more than just a series of presentations; it was a celebration of human curiosity and the relentless pursuit of knowledge. As guests departed, they carried with them not only a deeper understanding of the universe but also a sense of wonder and inspiration. The night was a testament to the power of education and the limitless possibilities that lie ahead as we continue to explore the cosmos.