Welcome to the June edition of DiRAC’s newsletter!

As the academic year ends, we have an exciting lineup of updates to share with you, showcasing the achievements and outreach made by our excellent team members.

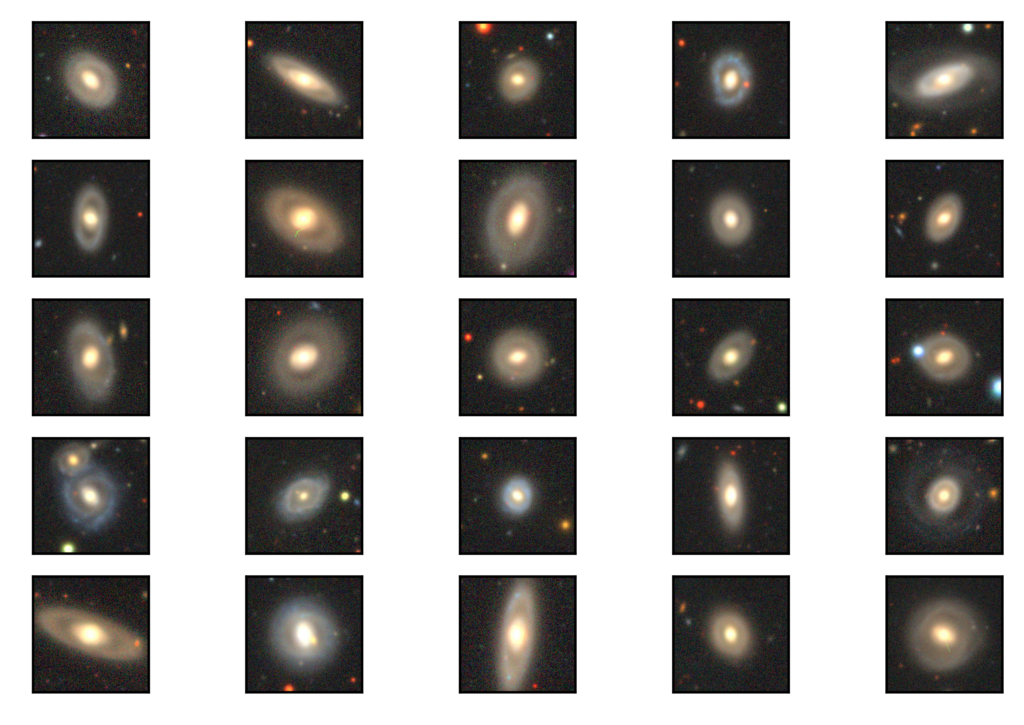

In March, our researchers had the privilege of sharing their groundbreaking discoveries at the captivating DiRAC Planetarium Event, showcasing our work ranging from astronomical software to mapping where water is in the solar system. Here, we give you a flavor of that work: a captivating research highlight from Bryce Kalmbach, DiRAC research scientist, and Harish Krishnakumar, a high school student from Tesla STEM high school in Redmond, showcasing their work on detecting rare ring galaxies using deep learning.

The anticipation of science from Rubin Observatory has also been a feature story on UW’s main website this past May.

Finally, we extend our heartfelt gratitude for your incredible support on Husky Giving Day. Your support enables us to continue the Summer Research Prizes for UW graduate and undergraduate students, for some of whom this is their first foray into astronomy.

So, grab a cup of coffee, sit back, and join us on this cosmic journey as we delve into the awe-inspiring world of astronomy.

Thank you,

Mario Juric

Director, DiRAC Institute

Professor, Department of Astronomy