At DiRAC, we work to understand the universe through data-intensive discovery. We build the world’s most advanced sky surveys, algorithms, and software to explore and understand the Universe. Over the next decade, our researchers and students will scan the sky for hazardous asteroids, discover interstellar comets, and search for new planets in our Solar System. Our codes will map the Milky Way, detect the most energetic explosions in the universe, and help understand Dark Energy.

Rubin Observatory network technician Guido Maulen installs fiber optic cables on the Top End Assembly of the telescope mount.

This work requires special telescopes and instruments to image the sky at a massive scale. The flagship instrument we’re helping build to enable this is the Rubin Observatory. Presently being constructed in Chile, starting in 2024 Rubin will collect and deliver the largest optical dataset ever collected: the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST). The LSST will gather data for over 17Bn stars, some 20Bn galaxies, quintuple the number of known asteroids, and increase the number of known dwarf planets by at least ten-fold. In scientific impact, it will be the ground-based peer of the recently launched Webb space telescope.

The LSST Camera: the largest astronomical optical camera. Each snapshot taken with the LSST camera consists of 3.2 gigapixels. To display a single image taken by this camera at full resolution would require nearly 400 4k TVs.

It was therefore incredibly exciting to view the nearly-finished LSST Camera earlier this month at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, sharing the experience with a group of DiRAC supporters and friends. Sitting at the heart of Rubin Observatory’s Simonyi Survey Telescope, the “LSSTCam” is the instrument that will capture millions of high-resolution wide-field photographs of the night sky that make up the LSST. It consists of 189 CCD sensors with 3.2 gigapixels in total and is capable of detecting light from the near ultraviolet to near infrared (0.3-1 μm) wavelengths. LSSTCam is the largest digital camera ever constructed: to display a single image taken by this camera at full resolution would require nearly 400 4k TVs. And at about 5.5 x 9.8 ft and weighing nearly 6200 lbs it’s closer in size and appearance to a jet engine than your typical DSLR!

With LSSTCam, the Rubin Observatory will collect over 2000 images of the sky each night, for 10 years, creating a dataset hundreds of petabytes in size. DiRAC’s LSST team has been writing software that will analyze those data in near real-time: within sixty seconds, it will alert the world to new asteroids being detected, galactic nuclei changing their brightness, or stars exploding or blinking out of existence. This stream of discoveries will write new chapters in our understanding of the Universe.

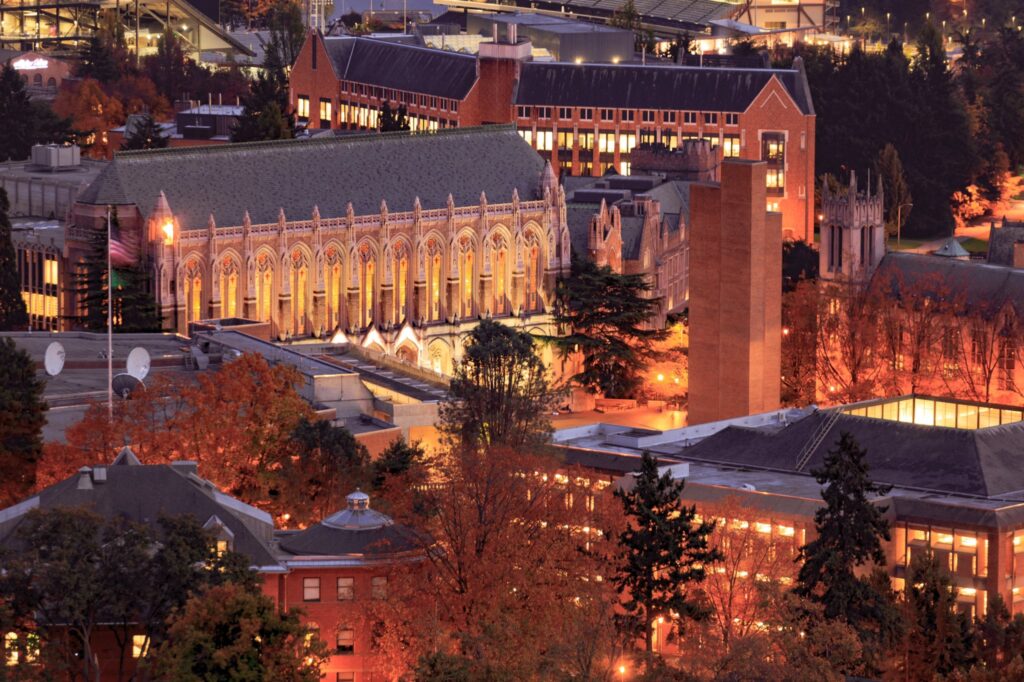

DiRAC Team visiting the LSST Camera:

Zeljko Ivezic (Rubin Construction Director), Jennifer Aydellot (UW Advancement), Mario Juric (DIRAC Director), James Davenport (DiRAC Associate Director) and Nikolina Horvat (DiRAC Operations Specialist).

For us on the team, seeing the LSST camera in-person and so close to completion was an emotional experience. A tangible sign of just how close we are to the end of the two-decade long journey to build a machine to capture the ultimate survey of the sky.

Rubin observatory roots run deep in Seattle. The University of Washington co-founded the project in 2003 (with U. Arizona, NOAO, and the Research Corporation) and since then, the it has grown to become the #1 national priority for ground based astronomy, a Bn$1-scale public-private partnership, and a large collaboration of a number of institutions. DiRAC leads the development of time domain image processing software, Solar System discovery codes, and observing cadence tools. And UW’s Prof. Zeljko Ivezic serves as the Director of the Rubin Construction Project. Notably, the project wouldn’t have happened without early Seattle-area supporters: funding by Dr. Charles Simonyi and Bill Gates built the observatory’s large 8.4-meter primary mirror and enabled initial research and development work.

We’d like to thank the entire team at SLAC, especially our LSST colleagues there – Profs. Aaron Roodman, Risa Wechler, and Dr. Vincent Riot – for this unique visit and their leadership in building this one-of-a-kind instrument. It’s taken over 20 years to go from the idea of Rubin/LSST to the present day. With the camera ready to ship to Chile next year, we’re one step closer to the beginning of a new era of astronomical discovery!