By Suberlak, Crenshaw, Kalmbach, Connolly

The Vera Rubin Observatory recently completed an extensive testing run using its engineering test camera (ComCam), marking a significant milestone toward full operations. Beginning as a dream in 1998, and under construction since 2015, this exciting moment marks the first time Rubin has observed the night sky. This crucial seven-week testing phase, which ran from late October to mid-December 2024, utilized ComCam—a smaller version containing just nine of the 189 CCD sensors that will be present in the final 3.2-gigapixel LSST Camera.

Members of the DiRAC Institute—Andrew Connolly, John Franklin Crenshaw, Bryce Kalmbach, and Chris Suberlak—played a central role in the testing, working on-site in Chile throughout the session. Their work focused primarily on Rubin’s Active Optics System (AOS), which maintains optimal image quality across the telescope’s 9.6 deg2 field of view by analyzing wavefront sensor data in real-time, calculating necessary adjustments, and controlling the positioning actuators on the primary and secondary mirrors despite environmental challenges like temperature fluctuations and mechanical stress. Successful operation of this complex system is necessary for Rubin to achieve its lofty science goals.

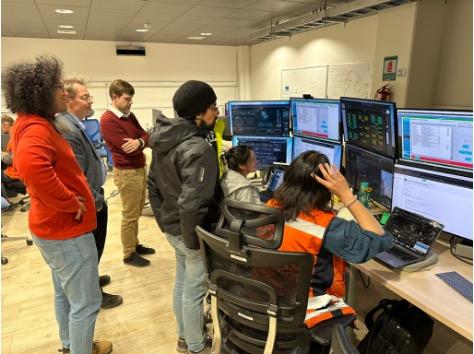

“35 out of the 52 nights of the engineering run featured at least one of the DiRAC team members on the summit. During one of the observing nights, Suberlak gave a quick online tour of the summit control room, answering questions via livestream for DiRAC guests gathered at the UW Planetarium. Much of the night’s work focused on implementing and testing new control software settings and evaluating how pipeline improvements affected image quality. These tests required close collaboration between AOS test scientists, observing specialists, and other team members, who provided rapid feedback to debug software and hardware issues.

No two nights felt dull or repetitive. One evening, a series of images revealed an unusual light pattern—something the team had never seen before. After two trips to the telescope dome, they discovered the culprit: a light source beneath the main 8.2 m mirror (M1/M3) had been left on due to a low-level software bug. On another occasion, thick clouds covered nearly the entire sky, and the weather forecast predicted slim chances of capturing useful images. Yet, as the night progressed, the sky unexpectedly cleared. Not only did the team manage

to take images, but the quality exceeded expectations—better than on many other nights—thanks in part to the AOS feedback loop.

We eagerly anticipate what the commissioning of the LSST Camera (LsstCam) will bring!