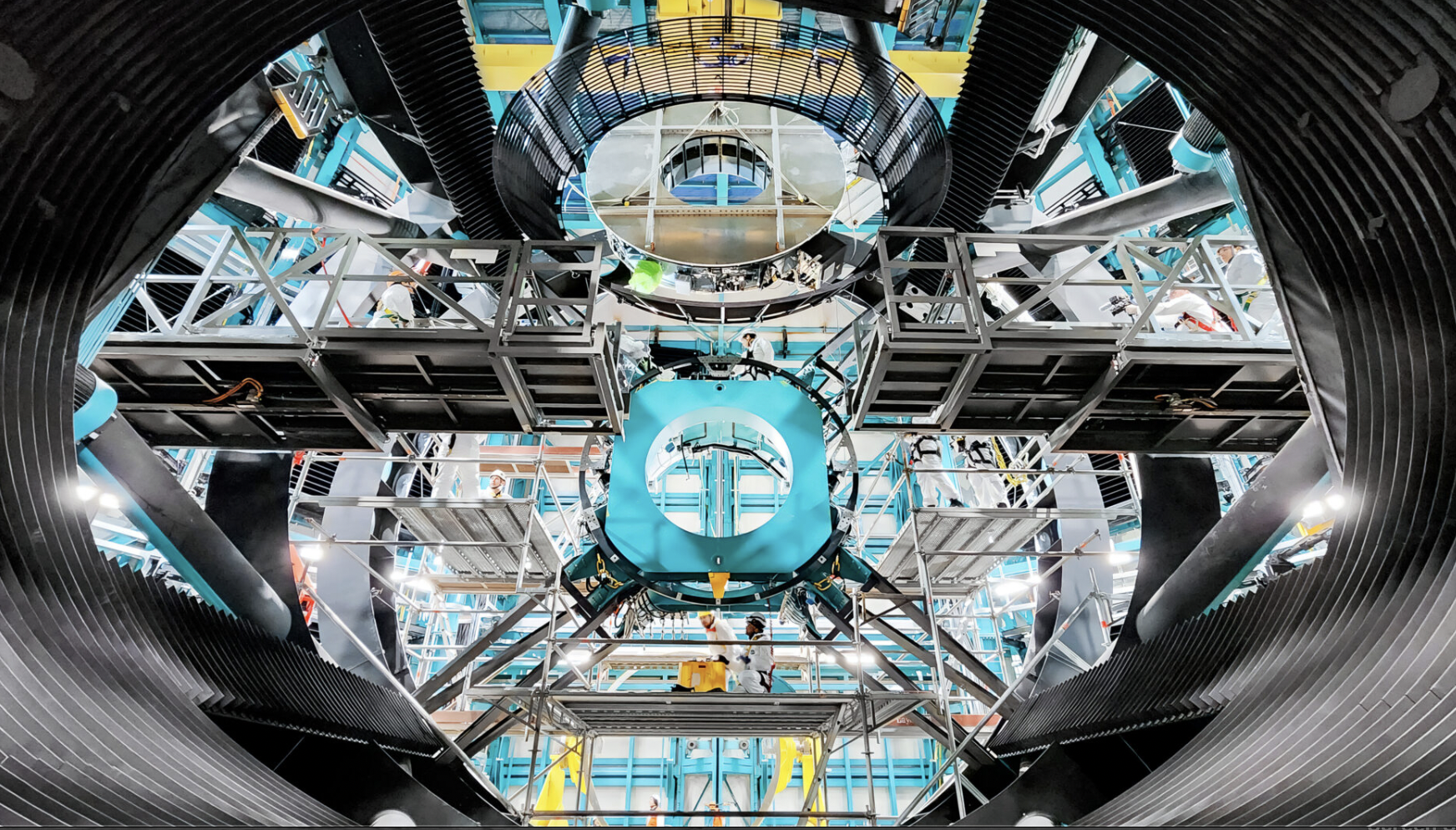

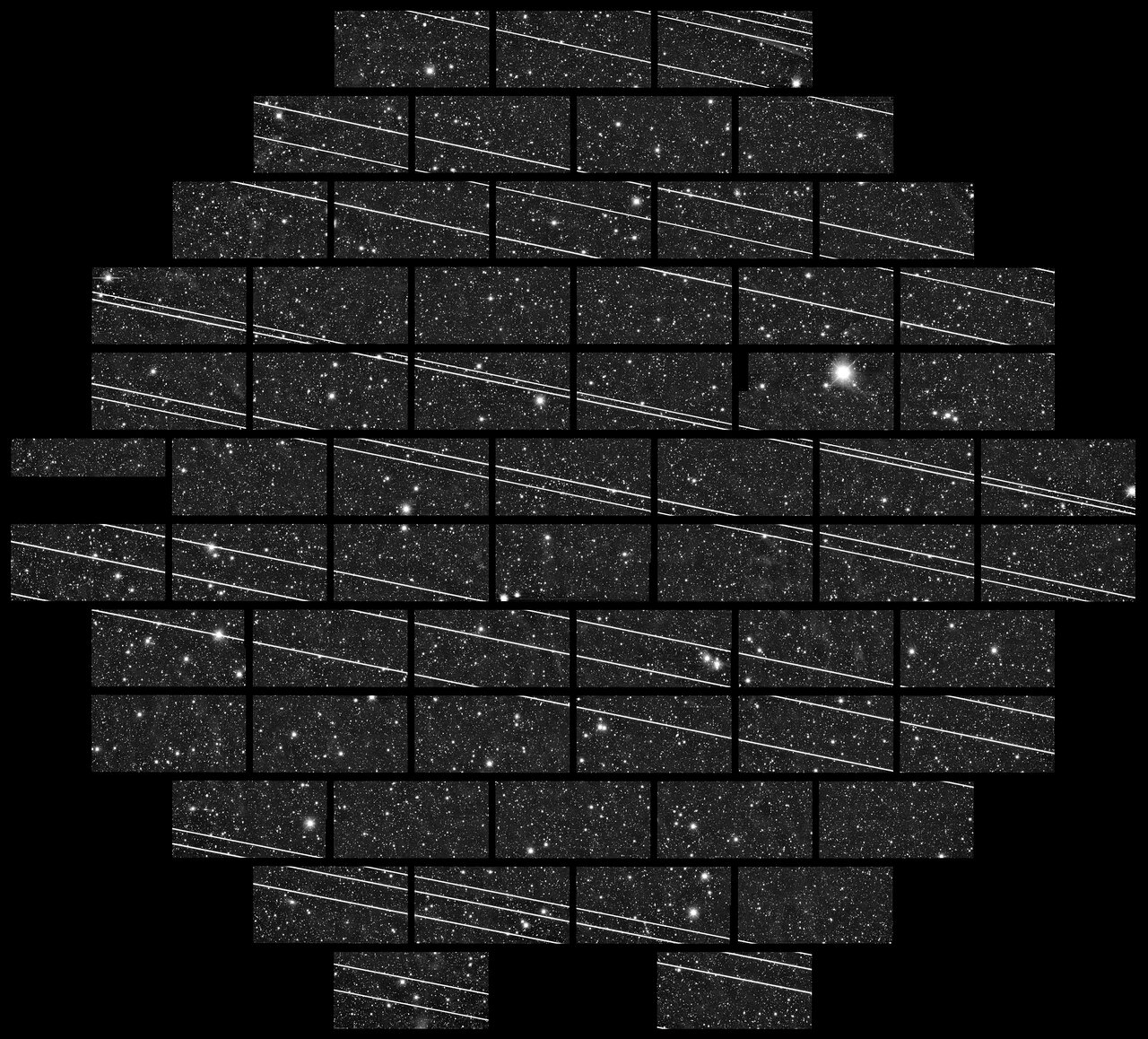

With the ramping up of the Simonyi Survey Telescope at the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile, Microsoft software architect Charles Simonyi joins a select group of scientists and technologists, policymakers and philanthropists who have had world-class telescopes and observatories named after them.